In December 2020, the City’s Committee on Housing and Real Estate passed an ordinance to the full Chicago City Council legalizing Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) for three years in five pilot areas comprising 22 percent of the City. Talk about dipping your toe into inclusionary zoning. But we’ll take it.

Buoyed by ULI Chicago’s advocacy, which convened multiple public and private organizations over the previous year, the City will allow homeowners to build coach houses, starting in May 2021, for the first time since 1957. With its affordable, modest size, a new generation of coach houses will bring diversity to housing stock that has only gotten more homogenous over time. Any increase in diversity catalyzes more resiliency, which our City sorely needs.

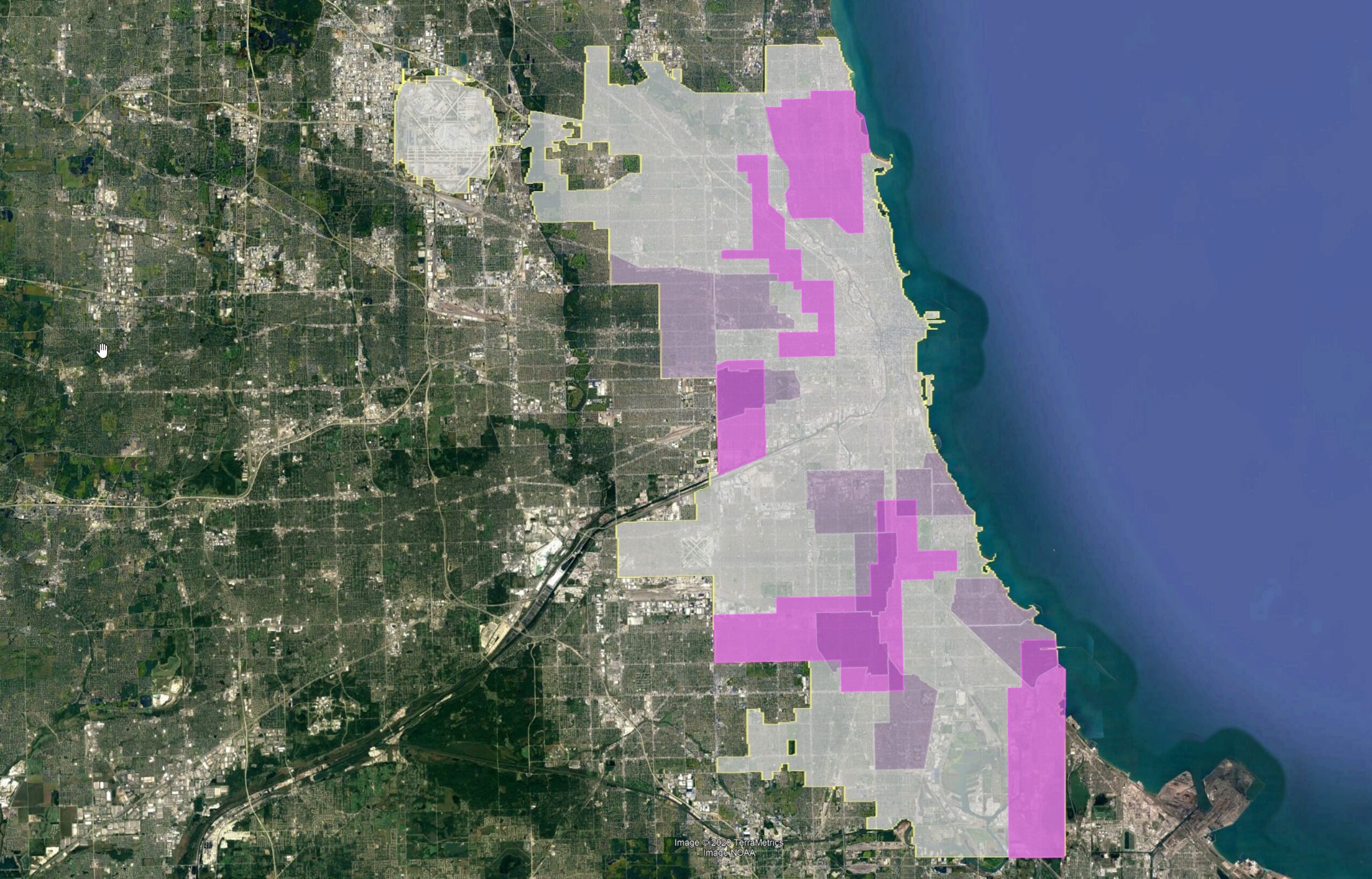

With the City’s laudable Invest South West program underway, we wondered if the ADU pilot zones aligned with its ten targeted neighborhoods. As evidenced by the illustration above, only 18 percent of the ADU pilot zones occur in communities slated for massive investment. This seems like a missed opportunity since ADUs make a compelling low-cost option for pioneers redeveloping areas suffering from decades of disinvestment.

Background

In 2003, the Metropolitan Planning Council advocated for the coach house’s return when the City was rewriting the Zoning Ordinance. That didn’t go anywhere. In 2018, we first advocated for Chicago to adopt ADUs when responding to the City’s Tiny Home RFP, envisioning them as an effective way to economically desegregate City blocks.

We drew on Chicago’s post-fire history when immigrants built family compounds on City lots over time. Many frame cottages that housed the working class were later relocated to the rear of the lot when families could afford a brick house. Then, extended family members or acquaintances rented it. With larger brick houses facing the street and tiny homes in the rear, the resulting neighborhoods offered economic diversity unheard of in modern times.

Coach houses should provide an opportunity for people across the economic spectrum to live in the City close to jobs, transit, and services. Cities like Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver led the way with legalizing ADUs since their high tech industries warped housing prices. But while the vast majority of ADUs being built in the Pacific Northwest are increasing housing density, they aren’t providing viable options for the working class. Often times, owners build ADUs for adult children priced out of homeownership in an affluent neighborhood. Is there a way for Chicago to be different? Let’s first consider who the occupants may be.

Who Lives in an ADU?

For many owners, a coach house can be the first or last home they own, either as a starter house or the final step in downsizing. Offering residents a chance to downsize within their neighborhood hedges against the displacement that has been a problem in Chicago. When faced with excessive taxes, owners could downsize to a coach house rather than moving from their neighborhood. Alternatively, a coach house could offer some owners additional rental income from an investment secured by the equity in the home they already own.

Either way, the coach house provides proactive housing safeguards for residents, particularly those on fixed incomes, so they can age in place when their neighborhoods gentrify or decline.

On the upsizing path, first time home buyers such as millennial college graduates with student loan debt can build equity with a purchase. Older adults recovering from homelessness could possibly relocate from a traditional SRO to rent an ADU. For others, coach houses could provide housing for aging family members and caregivers.

A New Role for the ADU in Chicago

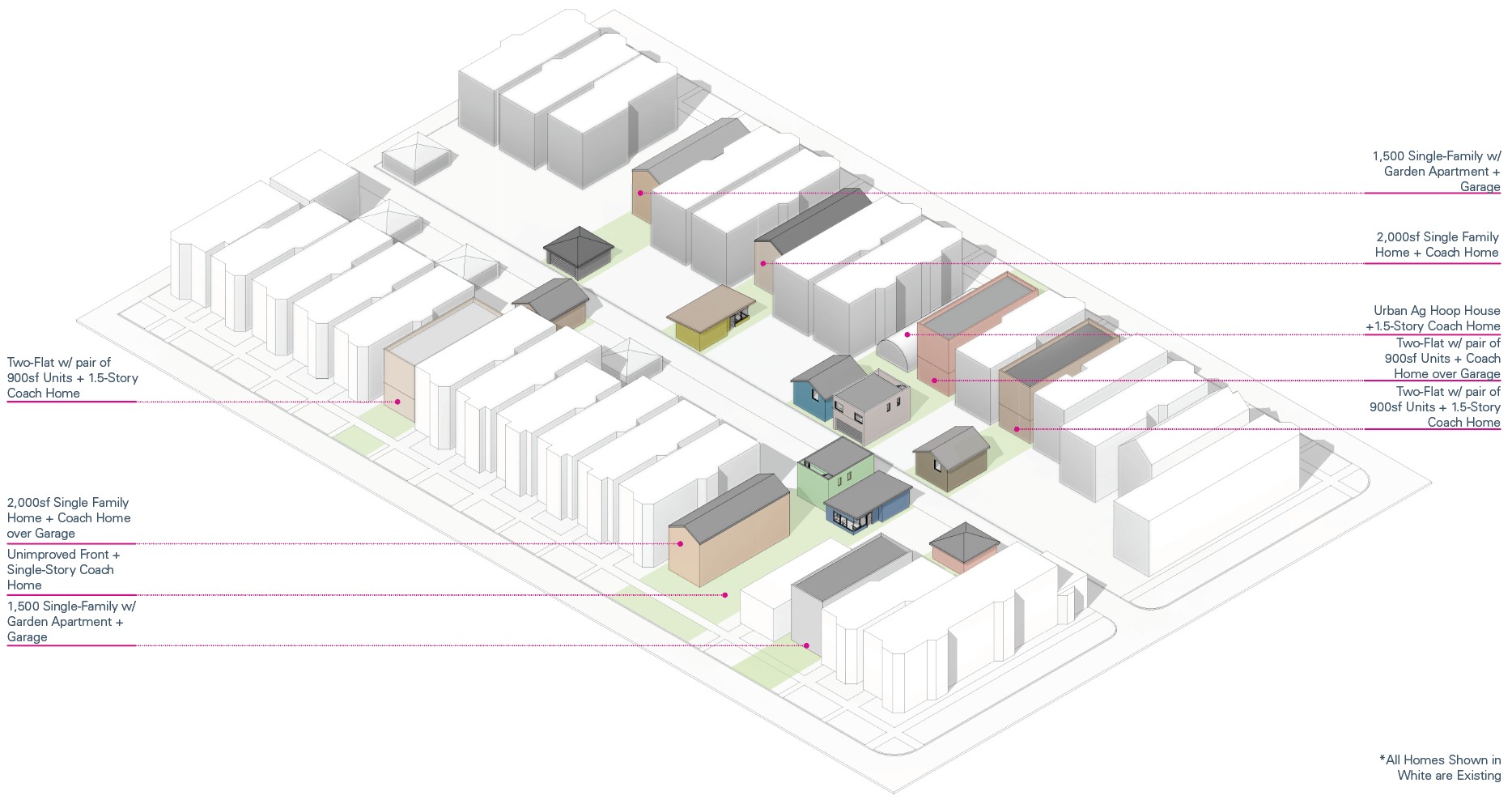

Rather than viewing coach houses as second-generation developments, we think Chicago should promote them to seed development in disinvested communities, especially ones with copious numbers of vacant lots. Entrepreneurial residents and local developers could be enticed to build coach houses with existing financing tools such as Low Income Housing Tax Credits, HUD’s Home program, and Illinois Affordable Housing Tax Credits. Chicago could jumpstart the trend by offering financial incentives to reduce the capital expense of building on the rear of a vacant lot.

The City could rebate the premium costs for extending street utilities, such as sewer and water, paid out of the City’s Neighborhood Opportunity Fund. These rebates would ensure that utilities would be sized for future front dwellings, making follow-on development more attractive. Similarly, alley utilities, such as electrical and communications, could be sized to serve future front residences, obviating future redundant drops. The City could rebate these premium costs, too.

Modern versions of “flat-pack” coach house kits could be shipped in bulk on semis that would deliver to multiple sites in the same zone on the same day. Individual property owners could share in an economy of scale through assurance contracts offer through a digital exchange, allowing entrepreneurial contractors to bundle multiple coach house projects in the same neighborhood. The City could streamline permitting and entitlement for the contractors to further de-risk the process.

As illustrated above, developers or owners can build coach houses before the building fronting the streets, to jumpstart reinvestment.

Alleys as a Blessing

When compared with cities like New York, Chicago’s alleys stand out as a blessing. Bolstered by initiatives like CDOT’s Green Alley program, Chicago’s alleys can transcend their utilitarian image to become an even more integral part of the City’s sustainable public spaces.

When private cars yield their dominance of alleys in the future, especially in Transit-Oriented neighborhoods, Chicagoans can reclaim alleys as places to reconnect with one another, reinforcing their stature as part of the City’s “connective tissue.” As Jane Jacobs wrote her influential 1961 treatise, “The trust of a city street is formed over time from many, many little public sidewalk contacts. Most of it is ostensibly trivial but the sum is not trivial at all.”

Chicago’s reborn neighborhoods can grow from their alleys outward, built around a core of affordable housing built for Chicago’s workforce. Unlike their predecessors, these coach houses will be accessible, single-story dwellings on-grade adjacent to green space. It could be the next riff on “Urbs en Horto.”