The best way to see a true cross-section of Chicago’s socio-economic structure is from the CTA Green Line, which bisects the city from its westernmost edge to its central core.

Ride the train from Harlem/Lake to Ashland/63rd Street, and you’ll pass bungalows, townhouses, currency exchanges, active and abandoned industrial parks, landscape suppliers, doggy daycares, nightclubs, lofted apartments, the United Center, and food trucks parked in empty lots. All the while, the skyline looms ever larger.

Long before you reach downtown, however, you come to one of Chicago’s hardest hit neighborhoods. Over the past half century, East Garfield Park lost more than two-thirds of its population to out-migration, from a high of 70,091 in 1950 to 20,881 in 2000. The median household income is roughly $25,000.

Today, you mostly find boarded-up brick two-flats, tire shops, and corner stores that sell clothes and cell phones. There are rib joints and bombed-out fire stations. Homes with sagging roofs, caved in from winter snow. Chain laundromats. Fast-food restaurants. Salvage yards whose razor wire is tinseled with the remains of plastic bags.

Designated a “food desert” by the Greater Chicago Food Depository, many families in East Garfield Park struggle to provide adequate nutrition and positive social experiences for their children. Among Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods, East Garfield Park is ranked seventh for incidence of heart disease, twelfth for diabetes, second for cancer, and last in very low birth weights, according to a 2007 study by the city’s Department of Public Health.

The area also has a large percentage of what is known as the working poor, individuals and families who are employed but still fall below the poverty line.

Within this bleak setting, however, the Garfield Park Conservatory and Garfield Park itself continue to draw visitors from around the world. The conservatory, designed by Jens Jensen and one of the largest greenhouse conservatories of its kind in the United States, is considered one of the city’s premier cultural institutions and one of its most popular destinations.

But due to a lack of sit-down restaurants and other gathering places, visitors have little opportunity to linger in the neighborhood As a result, these landmarks have become islands, isolated from their own community.

In 2009, I was brought on to lead the design of a somewhat radical social enterprise that planned to address the lack of access both to jobs that pay a living wage and to healthy food while capitalizing on the presence of the Garfield Park Conservatory, offering visitors a chance to spend time in the neighborhood.

Can architecture respond to this type of environment? Design, in some ways, may seem low on the list of priorities for a place so in need of major economic development. But what if architecture can provide an opportunity to respond to the systemic malnourishment of a city’s urban fabric? What if design can enhance that economic development and begin to impact a community’s quality of life?

Beyond theTriple Bottom Line

The project in question was a restaurant—on the surface, at least. In reality, it was much more than that. Inspiration Kitchens, named for the parent organization, Inspiration Corporation, would offer a chef training program, preparing individuals for work in the food-service industry, and provide healthy, seasonal cuisine in a neighborhood with virtually no sit-down restaurants.

The program planned to target formerly incarcerated individuals and others who faced barriers to employment and offer a unique program in which low-income families could eat for free. Free meal cards would be distributed through local advocacy groups and designed to look like credit cards, removing any stigma from receiving the meal for free.

One of the biggest hurdles for any social enterprise is money. Donations can be fickle. Grants can be highly competitive. State funding can arrive months after it’s been promised. Inspiration Corporation had been given an extremely generous gift to help cover operating expenses for up to five years, eliminating the pressure to immediately turn a profit. This money being earmarked for operations was good for the organization but meant that the construction budget was minimal, a fraction of what might be expected.

Add to this physical challenges like the building’s deteriorated condition, its proximity to the Green Line’s elevated train tracks, and the severe flooding that plagued the site, and we had our work cut out for us.

Good architecture responds to the complex social and economic constraints of its context. In fact, it’s well accepted that limitations breed creativity. Nowhere was this more true than at Inspiration. In fact, we were able to prove that good design can have long-term positive impacts on an organization’s bottom line.

People often talk about the triple bottom line, a framework that promotes calculating an organization’s performance based on not just the typical financial bottom line but also its social and environmental track record.

But this framework, while admirable, is limiting. Too many companies, nonprofits especially, assume that the most effective way to save money is to decrease the services offered, or in the case of a building, to lower their expectations. Financial solvency is attained at the cost of its mission.

Similar assumptions are made about socially and environmentally responsive design. As a building becomes greener, or more responsive to a community, its price tag, many assume, also increases.

At Inspiration Kitchens, we strove to subvert this thinking. Our experience has taught us that rather than treat these things as individual pillars that are measured independently, they should be seen as interdependent, part of an ecosystem. Social and environmental performance are integral to financial success.

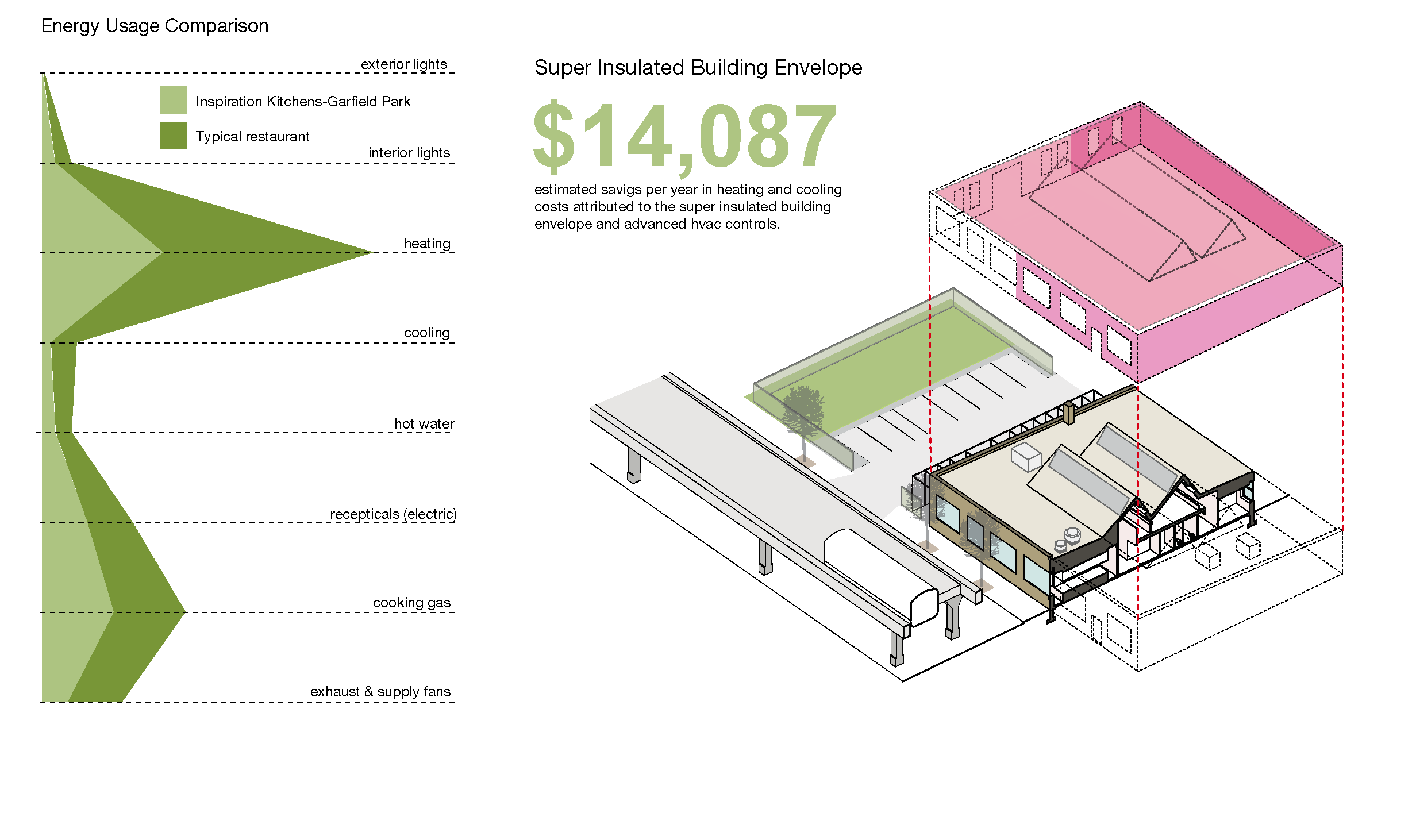

On a practical level, this meant putting the bulk of the budget toward a high-performance building envelope, which in Chicago’s variable climate is the best way to save energy and therefore operating costs. We also applied for and received grants from the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation which funded the addition of a cutting-edge variable speed exhaust system for the kitchen and rooftop solar-thermal panels, which provide 100% of the restaurant’s hot water, further offsetting costs.

These types of green features not only pay for themselves but eventually save the organization thousands of dollars a year. That’s money that will go back into the program. That’s how good design impacts the bottom line.

Lessons from Around the World

I grew up in Jamaica. Measured by the standards of the country, my family was probably lower-middle class. We lived on three acres, and my mother was constantly thinking up ways to make more money. One year she grew and sold roses. The next year she raised chickens. Then planted strawberries. She never made much, certainly not enough to alter our living situation, but enough for small things such as airfare and lodging for a short trip to the South American country of Suriname, a requirement for my undergraduate architecture studies.

I didn’t realize how little we had until we moved to the U.S. when I was 21. By the time I attended graduate school at UIC, I’d begun to see the social impact architecture could have.

In our second semester of graduate school, we focused almost exclusively on affordable housing. Several of the professors were active in the social architecture scene, and when I got the chance to study outside the U.S., I traveled for a month through several South African townships.

I’d grown up hearing about apartheid, the policy of racial segregation that plagued South Africa for nearly 50 years in the mid-20th century. When I arrived, it had been exactly ten years since the end of the apartheid era. I wanted to gain an understanding of the role of architecture in resource-starved communities.

What I learned is that social change takes a long time, certainly more than 10 years. I also learned the value of listening.

East Garfield Park is not South Africa, and it is not Jamaica. The poverty in Chicago is distinct, but there are similarities. For one, residents are oftentimes distrustful of outsiders, organizations, and government agencies, understandably so. This is just one challenge an architect must overcome when working in communities like East Garfield Park. Too many residents have been hurt by bad policy decisions and by those who I have intended to help.

Another similarity is that resourcefulness is a way of life. We tried to bring that spirit to Inspiration Kitchens. Architecture does not have to be expensive as long as it’s creative, and the key to creativity is getting your hands dirty.

Inspiration taught me that there’s always an alternative if you’re willing to look for it. If a detail we deemed important was too expensive, we found a way to make it ourselves. We wanted color-changing LEDs on the exterior of the main entrance, for instance, so that the illumination could change with the seasons, just like the restaurant’s menu. But the lighting was too expensive. So we fashioned our own, using regular LED lights and the kind of colored gels that theaters use during productions.

We did the same thing with the windows. Every few minutes, the Green Line passes within feet of the building. The noise, if unabated, would be highly disruptive. The obvious solution was to purchase acoustic windows, the kind airports use to minimize the noise inside terminals. But these windows were again too expensive. The science behind them, however, is fairly basic, so we decided to engineer our own. Our windows are more efficient at blocking sound than those installed at airports but were built for a fraction of the cost.

Although this sort of problem-solving sounds easy after the fact, in the moment it requires a hands-on approach that allows for creativity and exploration. More than anything, it requires a commitment to the good of the organization and the community.

My favorite feature at Inspiration is the window that looks into the kitchen. Even from the entrance, you can see the men and women working, training to be chefs and cooks, serving delicious, healthy food. They are the reason Inspiration exists, and by making them visible, they become an advertisement for the program and a symbol to the community that change is possible.