There are many ways architecture can adapt to its environment: automation systems learn an occupant’s habits, moveable walls turn office spaces into event venues, and shades and solar arrays move to track the sun.

But adaptability isn’t always—or ever, really—about technology. It is primarily about improving the occupant’s experience and purpose, which, though we may not think about it, change throughout the day. Despite this, we often create static, single-purpose environments that in no way acknowledge, much less respond to our regularly changing needs.

Architects can, however, with creativity and a thorough understanding of the user’s purpose, create spaces that respond to ever-shifting demands in real time. This was the modus operandi at the Wolcott School, Chicago’s first high school dedicated to students with learning differences.

According to the National Center for Learning Disabilities, approximately 2.4 million high school students (roughly five percent of the student population) are diagnosed with disorders such as dysgraphia, dyslexia, and auditory-processing, which can interfere with a child’s reading, writing, and math.

These learning disorders, or differences, become major hurdles to a child’s education, especially in a one-size-fits-all institution where teaching is done through direct oral instruction—known colloquially as the “talking head.” When a child’s learning suffers, other less-measured areas often suffer as well, including self-esteem and social development. The limits of the prototypical environment end up leaving gifted students floundering and feeling isolated.

My own son, now a college graduate, grew up with executive functioning difficulties and an auditory-processing disorder. He struggled with comprehension when the teacher was talking and had a difficult time solving problems in a logical fashion. A “talking head” presents information in the worst possible format for a student who struggles with audio processing. Even with an IEP (individualized education plan), he was only nominally successful because an IEP can only supplement a school’s one-size-fits-all model.

Jennifer Levine and Jeff Aeder founded Wolcott in response to their daughter Molly’s dyslexia. They envisioned a learning environment designed to support students who learn in different ways.

Jeff and Jennifer formed an advisory council and asked us to help them think through what such a school should look like. How big are the classrooms? How is the building laid out? And, crucially, how can the building adapt to daily needs?

In most schools, a teacher’s domain is a single general-purpose classroom. Any specific types of learning spaces outside the classroom are shared and must be reserved ahead of time for the entire class.

At Wolcott, students’ needs vary greatly, and instructors need environments that can address them in real time. Even with just 10 students per class, many disparate needs arise simultaneously, not to mention the needs of specialists who come in from time to time to work with students individually.

How can a learning environment accommodate such variety?

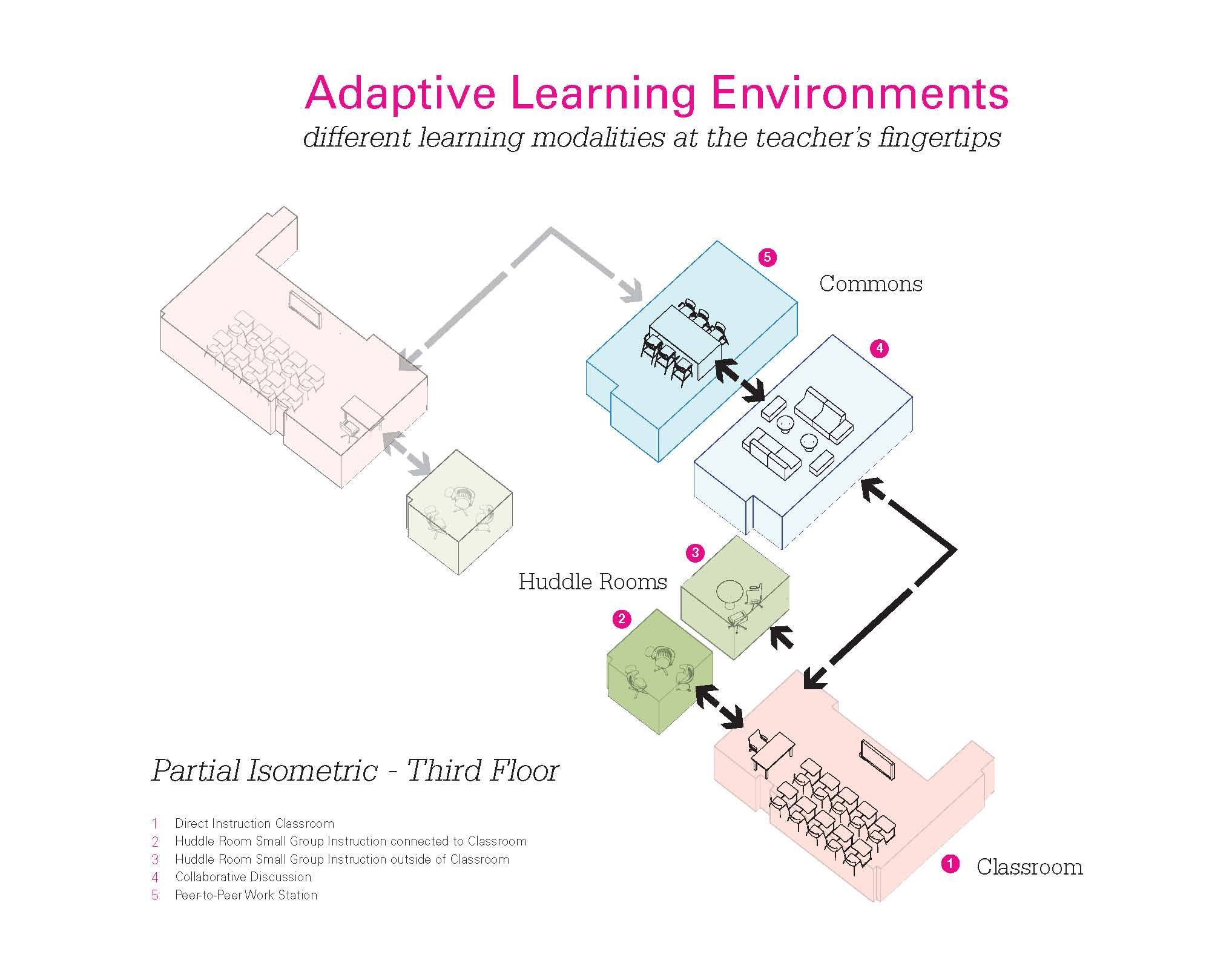

Our solution interconnected a variety of learning spaces that instructors can recruit on an impromptu basis, including semi-private huddle rooms, informal and formal peer-to-peer collaboration spaces, and areas for solitude, all arranged around the traditional classroom. It was important that these spaces have low thresholds to entry, both psychologically and physically. Locating them near the classroom, connected visually and at times separated only by a partial wall, prevents their becoming stigmatized.

Students and teachers can easily navigate the entire palette of learning spaces. The regularity of their use normalizes the fact that kids learn differently.

Students are not escorted from the “normal” classroom (as happens when specialists remove students for one-on-one learning) but make use of the spaces that work for them, with a specialist or on their own. Students remain part of the group even if they seek solitude periodically.

Outside these groupings, every floor offers a central area oriented around a historic fireplace. This serves as a gathering place, an informal and formal collaborative area, and a space for solitude. Each is furnished to encourage a variety of uses and can be rearranged to suit students’ needs. And because these areas occupy the same central location on each floor, they serve as landmarks that make navigating the school intuitive.

Much the way a student’s education is personalized, Wolcott’s building follows suit. Unlike at a traditional school, the student’s footprint is larger and more varied than the instructor’s. This is adaptability with a purpose.

Obviously, what works in one school won’t work everywhere, but adaptability need not be limited to high-tech, high-cost systems. At Wolcott, adaptability is baked into the architecture, thanks to innumerable discussions with educators, administrators, and experts.

The unique educational mission drove the design from the beginning, and resulted in Wolcott succeeding in its mission to provide a rigorous yet flexible academic environment for children with learning differences.