To rejuvenate its neighborhoods, Chicago may want to consider importing an idea emerging from the hinterlands. The idea isn’t exotic. It’s downright retro.

In America’s farmland, startup IndigoAg is promoting regenerative agriculture at scale to capture all the carbon emitted in the atmosphere in modern times. By merely increasing the carbon content of the average farm’s soil by 2% to preindustrial levels, they propose to avert climate change. But farmers will have to abandon the modern agricultural practices born in the 1950s. The practices have destroyed the soil, its biotic diversity, and its natural ecosystem. We need to turn the clock back.

A Parallel Path for Planning

What if Chicago adopted a parallel path, and reversed planning policies passed in the 1950s which promoted monocultures of housing, manufacturing, and business? The zeitgeist of the early modern era sought a rule book to facilitate progress. But has the modern zoning rule book improved economic diversity, land, and ecosystem services for the City? Or has Chicago suffered consequences from the same market thinking that turned everything we grow into a commodity?

Most zoning laws born in the modern era segregate uses and, in some cases, even regulate minimum sizes of buildings. These laws exaggerate exclusivity. Some cities like Minneapolis are starting to reverse their exclusionary zoning laws, noting that they pose hurdles to creating the neighborhoods they want. Neighborhoods built as monocultures aren’t producing the diversity that modern cities or its constituents need to reach their potential. One of the primary benefits of a contemporary city is its ability to innovate from the diverse ideas that collide within its footprint. A city engineered for monocultures makes leveraging that diversity difficult. But now, to complicate matters, cities are struggling with housing everyone. Affordability is threatening the loss of the talents and potential of those unable to pay.

Metropolises like San Francisco are suffering acutely. As its residents can attest, housing shortages there have escalated into a crisis. Commuters willing to traveling unreasonable distances to find affordable homes can no longer find them. Residents can’t be displaced any further. As modern cities grow, citizens need to retain their mobility, both physical and economical, within the city, without surrendering their franchise.

Post War Market Thinking

As Michael Sandel warns in “What Money Can’t Buy,” market thinking, which treats everything as a purchasable commodity, can dilute social values. It’s no coincidence that modern zoning was born at the same time market thinking exploded. Market thinking doesn’t focus on the common good. It focuses on individuals.

Monocultures of housing created by modern zoning districts actively prohibit economic diversity. In sprawling suburbs, this wasn’t a problem since more land could be consumed to fulfill any need. But older landlocked cities are a different story.

Amid the affordable housing crisis, most cities find their hands tied by market driven zoning instead of liberated by it. Instead of enabling the social equity politicians espouse, exclusionary zoning laws exacerbate inequality.

In her July 29, 2019 column, New York Times columnist Emily Badger lamented the current villainization of developers, even though most critics live in buildings built by one. In mature cities like Chicago, developers must contend with escalating costs for infill projects. Costs for soil remediation, assembling parcels, avoiding buried infrastructure, and battling neighbors intent on the status quo add up. To make matters worse, impact fees and mandatory requirements to fix the city’s aging infrastructure escalate costs further, while property tax rates fail to keep pace. It’s no wonder that most new development, built without subsidy, is out of the economic reach of mere mortals.

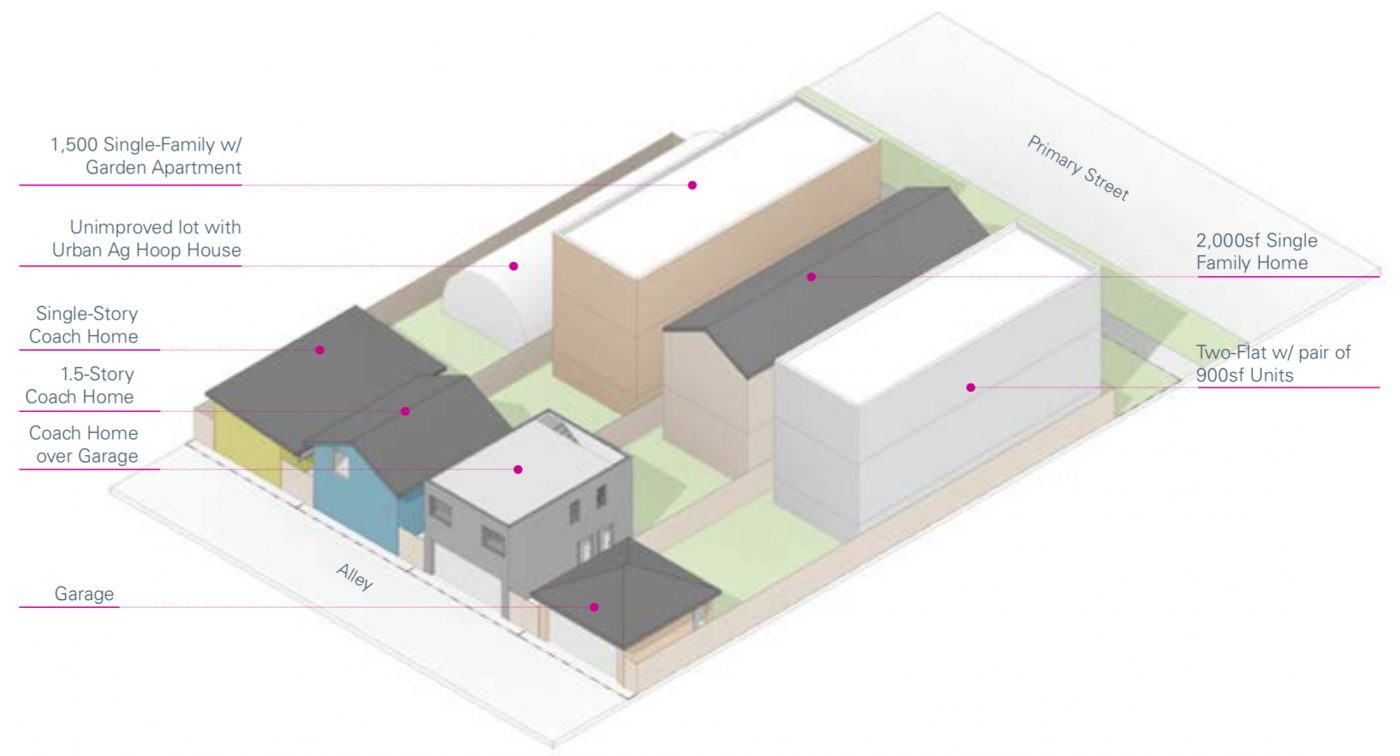

Ms. Badger concludes her column by noting that codes often prohibit small infill projects like Alternative Dwelling Units (ADUs), which offer older cities a chance at affordable housing. Chicago is a perfect candidate for ADUs, since the economic diversity it once offered within the same block existed here long before modern zoning precluded it. You can see our take on ADUs in Chicago, which we call Coach Homes, here. Encouragingly, the City is now entertaining ADU legislation. Our fingers are crossed.

Regenerating Instead of Fixing

Adopting ADUs in older cities could be a good first step toward Regenerative Zoning. Not only can ADUs promote economic diversity but they can seed new development on vacant lots, too. Like its agricultural cousin, Regenerative Zoning won’t seek to mitigate problems created by the previous generation of market thinkers. Instead, it will supplant current regulations with a model that considers the common good, returning to the more natural patterns of a healthy ecosystem.

In its most mature form, Regenerative Zoning will unleash the full potential of polycultures, where different uses and occupants coexist in the same place to mutual benefit. Homes of all sizes will coexist with restaurants and digital manufacturing on the same block. The resulting neighborhoods will not end up as one-size-fits-all commodities. They’ll be vibrant places. After shifting from mass production to mass customization, neighborhoods will offer residents affordable personalization unheard of in the modern era.

We can turn our planning clock back. Economic diversity can return to our neighborhoods. Cities can become problem solving crucibles where diverse ideas posited by diverse constituents collide more frequently, resulting in a healthier ecosystem for everyone.